Female brains are delicate and more vulnerable to concussions than the brains of men – study

Wednesday, December 27, 2017 by Tracey Watson

http://www.realsciencenews.com/2017-12-27-female-brains-are-delicate-more-vulnerable-to-concussions.html

Women have fought long and hard for the right to be viewed as equal to men. Most of us would be loathed to admit that we are more fragile or delicate than men in any way, but unfortunately, there are some biological ways in which women are not quite as tough as the opposite gender.

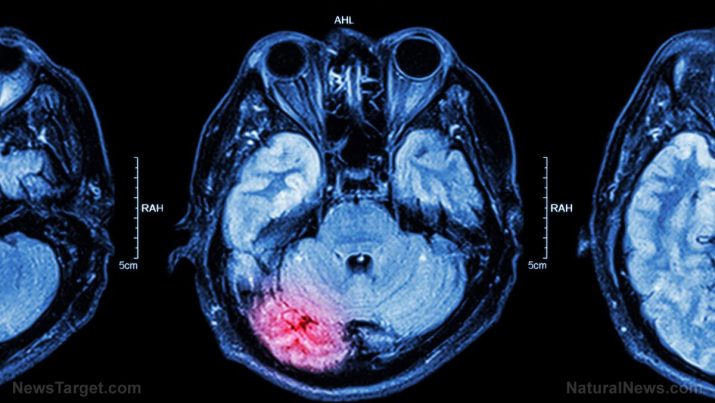

A recent study by neuroscientists from Penn Medicine, for example, found that women have leaner nerve fibers in the brain, making them more susceptible to concussions than men. The study was published in the journal Experimental Neurology.

The research team performed several tests on rat and human neuronal cells, and found that female axons – long, slim parts of the neuron that are responsible for relaying messages and are viewed as the brain’s “electric grid” – are smaller than men’s. Female brain axons also contain fewer microtubules, which are like the pathways that transport molecules up and down the axons.

The scientists found that when exerting an equal amount of pressure on female and male axons to simulate a traumatic brain injury, the female axons were more likely to break.

It is believed that it is this breaking that results in the symptoms associated with concussion, including dizziness, confusion, headaches and temporary loss of consciousness. (Related: Stay up-to-date with the latest breakthroughs at Medicine.news.)

This research helps explain the findings of a study released earlier this year at the American Academy of Neurology’s 69th annual meeting. That study examined 1,203 male and female athletes who took part in sports like basketball, soccer and football between 2000 and 2014. A total of 228 of the participants were injured and suffered a concussion during that time – 23 percent of them women and 17 percent men. The study found that overall, female athletes are 50 percent more likely to sustain a concussion than male athletes.

And now we know why.

“The paper shows us that there is a fundamental, anatomical difference between male and female axons,” explained Douglas H. Smith, MD, director of the Penn Center for Brain Injury and Repair. “In the male axon, there are a great number of microtubules, which make the entire structure stronger, whereas in female axons, it’s more of a leaner type of architecture, so it’s not as strong.”

Penn Medicine News explained more about what causes concussion:

When someone suffers a traumatic blow to the head, the axons are stretched at a very rapid rate. While the axons typically stay intact, their microtubules can break under the strain. The faster they stretch, the stiffer the crosslinking proteins known as tau become. This transfers high stress onto the microtubule that can result in them rupturing, setting off a molecular imbalance.

Once the brain’s “transport system” is disrupted in this way, things quickly go haywire, creating a buildup of sodium and calcium ions. When calcium levels reach a certain level, a self-destruct process is triggered, unleashing protein-breaking enzymes which damage the structure of the axon.

Tests revealed that 24 hours after such an injury, female axons exhibit significantly more swelling and a greater loss of calcium signaling function than male axons.

The researchers concluded:

It is conceivable that under the same level of mechanical loading during head impact, axons in female brains may be more susceptible to damage than axons in male brains due to fundamental differences in axon ultrastructure.

While most people appear to recover from a concussion within a few days, the damage such injuries cause to the brain can actually linger for decades, according to research presented to the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) annual meeting in 2013.

Medical News Today reported that when the brains of healthy athletes were compared to those of athletes who had suffered concussions three decades earlier, those who had undergone head trauma were found to struggle with memory and attention problems, and to exhibit symptoms similar to the early signs of Parkinson’s disease. (Related: Teenagers who experience a concussion have a greater risk of developing MS later in life, according to new study.)

Athletes who return to the game too soon after suffering a concussion also risk serious and severe brain damage.

Clearly, more needs to be done to protect both male and female athletes from suffering concussions in the first place.

Sources include:

Tagged Under: Tags: Athletes, Brain Injury, brains, concussion, female athletes, females, gender, goodhealth, goodmedicine, goodscience, males, neurology, research, women