New NASA mission could unveil more secrets of the universe

07/09/2019 / By Edsel Cook

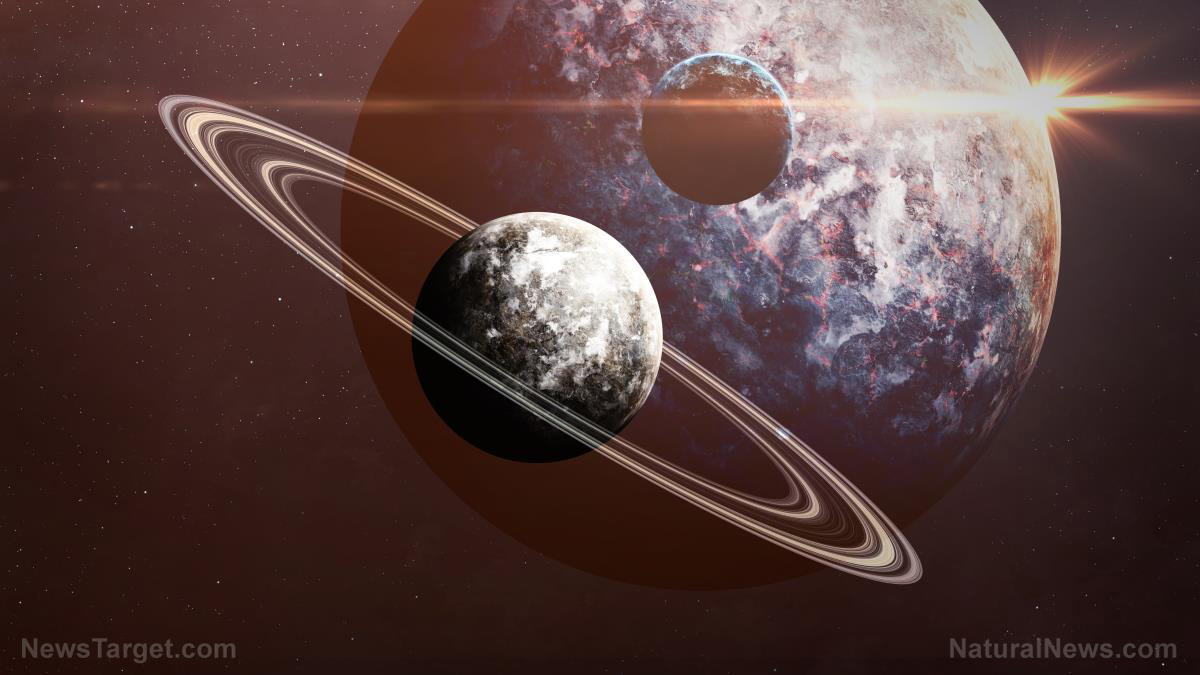

Move over, Hubble – the upcoming Wide-Field Infrared Survey Telescope (WFIRST) offers researchers the best look at the universe. An extensive analysis of the space telescope’s capabilities predicts that it may discover up to 1,400 new exoplanets around other stars.

NASA and researchers designed WFIRST to seek out new planets outside the solar system. It will improve the accuracy and efficiency of the search for extraterrestrial life.

Furthermore, the space observatory will also study dark energy. A better understanding of the invisible force that permeates everything may help researchers learn more about the expansion of the universe, which is supposedly powered by dark energy or dark fluid.

Researchers at Ohio State University (OSU) calculated the potential reach of the WFIRST mission, which was still in the planning stages. The university made considerable contributions to the project ever since NASA first came up with the idea. (Related: Weird science: Did a mirror image of the universe exist after the Big Bang?)

New space telescope will use gravitational microlensing to search for new exoplanets

On the subject of exoplanet hunting, WFIRST would continue the work of the retired Kepler space observatory. Kepler spotted more than 2,600 planets outside the solar system during its operational life.

WFIRST may not find as many planets, but it will be able to spot the ones that are further away from the primary star.

“Kepler began the search by looking for planets that orbit their stars closer than the Earth is to our Sun,” explained OSU researcher Matthew Penny. “WFIRST will complete it by finding planets with larger orbits.”

The new space telescope employs gravitational microlensing for its planet-hunting mission. When starlight passes behind a planet or star, the gravitational field of the celestial body bends and magnifies the light seen by the telescope.

With the help of this microlensing effect, WFIRST will spot exoplanets at more stellar distances than Kepler’s transit method or other planet-detecting approaches.

The drawback to the microlensing technique is its reliance on planetary or stellar gravity bending the light emitted by another star. The gravitational effect only lasts for a few hours, and it may take millions of years before the process repeats itself. WFIRST will need to keep constant track of the many millions of stars at the heart of the galaxy.

Penny also believes that around 100 of the exoplanets found by WFIRST may turn out to either have a mass less than or similar to Earth’s.

WFIRST will map out the Milky Way faster than Hubble ever did

WFIRST is also tasked with surveying the Milky Way and other galaxies. It will perform the job of the Hubble Space Telescope at a much faster rate.

The space observatory will scan a larger swathe of the universe compared to Hubble, James Webb, and other earlier telescopes. It also boasts of a higher resolution which can spot smaller details.

“Although it’s a small fraction of the sky, it’s huge compared to what other space telescopes can do,” Penny explained. “It’s WFIRST’s unique combination — both a wide field of view and a high resolution — that make it so powerful for microlensing planet searches.”

He theorized that WFIRST will be able to spot new types of planets during its microlensing survey. Researchers might use the data to determine how frequency a type of planet formed.

Planet-hunting studies have identified almost 700 planetary systems with at least two exoplanets. They also found around 4,000 individual worlds. The orbits of most of those exoplanets were much smaller than that of Earth.

Penny also expressed high hopes for the infrared sensor of the WFIRST. Infrared light can penetrate the veil of cosmic dust between Earth and the densely-populated center of the Milky Way.

Sources include:

Tagged Under: astronomy, Center of the Milky Way, discoveries, exoplanets, Hubble Space Telescope, Milky Way, outer space, space observatory, space telescope

RECENT NEWS & ARTICLES

COPYRIGHT © 2017 REAL SCIENCE NEWS