Valleys and channels on Mars reveal evidence of ancient groundwater

07/13/2019 / By Edsel Cook

The deepest parts of the craters that dot the dusty Martian landscape conceal channels and valleys carved out by the passage of liquid water eons ago. European researchers consider them to be signs that Mars possessed a massive groundwater system in its distant past.

Furthermore, the European Space Agency (ESA) research team uncovered evidence of mineral deposits in those craters. On Earth, those same minerals contributed to the appearance of organic life.

In a recent statement, ESA researcher Dmitri Titov stressed the importance of these findings. The formations and minerals mark the regions that had the best chance of harboring evidence of past life on Mars.

The discovery was made by the agency’s Mars Express space probe. Orbiting the Red Planet since 2003, it uncovered geological proof that Mars once hosted a large network of subterranean lakes. Branching channels serve as the connections between these underground bodies of water.

NASA earlier theorized that the Martian underground might contain giant cliffs of ice.

The surface water of ancient Mars moved underground

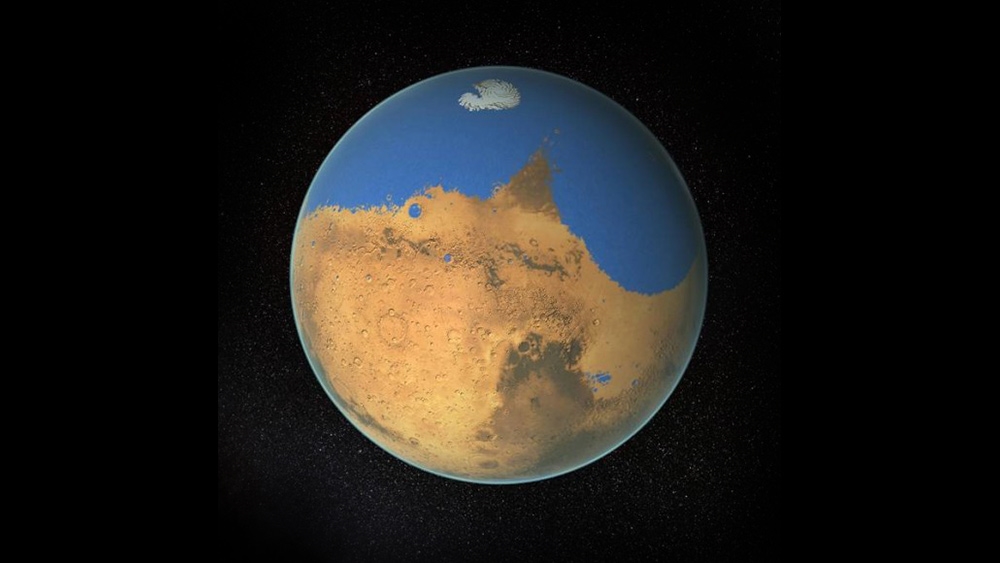

“Early Mars was a watery world,” said Francesco Salese, a Dutch researcher from Utrecht University. “But as the planet’s climate changed, this water retreated below the surface to form pools and ‘groundwater.’”

Researchers argued over the amount of water present on the surface of Mars. They also disagreed about the role played by the liquid.

Using the sensors of the Mars Express orbiter, Salese and his colleagues tracked the migration of water from the surface to below the red soil of Mars. They announced the first geological evidence that Mars used to have a groundwater system throughout the planet.

Recent studies indicated that Mars used to enjoy warmer temperatures in the past. It seemed that the atmosphere of the planet during that time was thicker and retained more heat. The temperatures appeared to be congenial for the movement of liquid water on the ground.

In the new ESA research effort, Mars Express scanned 24 deep craters in the northern half of the planet. The bottoms of the formations reached depths of 2.5 miles (4 km) beneath the value used as the Martian “sea level.”

Mars currently does not have any sea on its surface. But it used to have one. Instead, researchers calculated an approximate sea level using atmospheric pressure and elevation.

“We think that this ocean may have connected to a system of underground lakes that spread across the entire planet,” remarked D’Annunzio University researcher Gian Gabriele Ori, the co-author of the paper. “These lakes would have existed around 3.5 billion years ago, so [they] may have been contemporaries of a Martian ocean.” (Related: Geological curiosity: Mars “blueberries” reveal what ancient Mars may have looked like.)

Deep Martian craters hold minerals important for basic life

They reported finding evidence of carbonates, silicates, and more than one type of clay in the five deepest craters surveyed by Mars Express. The minerals served as basic ingredients for organic life on Earth, so their presence suggested that ancient Mars also possessed the ingredients to support simple organisms.

Before their latest Mars-related announcement, ESA also released photographs of the southern highlands area of Mars. The rock formations in the region are billions of years old and have undergone considerable erosion over the eons.

Mars Express took snapshots of an area found between the Hellas and Huygens craters. Despite the destructive effects of erosion, several valleys displayed dendritic structures – familiar shapes that resembled trees – and riverbeds on Earth.

The dendritic structures suggested that the Martian surface used to be covered in water. The new ESA study suggests that much of that water went underground and formed subterranean lakes.

Sources include:

Tagged Under: ancient Mars, breakthrough, cosmic, discoveries, groundwater, Life on Mars, Mars, outer space, planets, red planet, Space, space exploration, space research, water, water on Mars

RECENT NEWS & ARTICLES

COPYRIGHT © 2017 REAL SCIENCE NEWS